"Delusion Angel," a poem in "Before Sunrise" (1995)

"Before Sunrise" (1995) holds a special place in my heart. If you know me, you might have the unfortunate experience of listening to me babbling about it.

There is nothing much happening in the film, really. Just talking and walking. Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Céline (Julie Delpy) meet on a train in Europe. He persuades her to get off the train in Vienna. They spend the night walking around the city and getting to know each other. Taking place over the course of one night, the limited time together leads to their openness and honesty, both believing they will never see each other again. The two characters’ ideas on love and life are gradually revealed. The two are very young and innocent, romantics but not without some doubts at hearts.

One aspect of the film intrigued me, and that is references to James Joyce. The film occurs on June 16th, the day on which Joyce’s Ulysses is set, “Bloomsday.” Like Ulysses, the film takes place on a single day, involves traversing a single city (Dublin/Vienna), and includes a visit to a graveyard. Jesse’s real name is James, and he is an aspiring writer. June 16th is also the day Joyce met his future wife Nora Barnacle, whom he managed to talk into running away with him to Paris. While at university James Joyce translated a play by the German writer Gerhart Hauptmann; the play is...

Continue ReadingPoetic Language of Charles Darwin in “The Origin of Species”

Much scholarship has been done to explore Darwin’s writing as literary works such as Hyman’s The Tangled Bank, Beer’s Darwin’s Plot, and more recently, Levine’s Darwin the Writer. The latter even claims that the most important English literature written the nineteenth century is Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species (1859), usurping the role of the canonical texts such as Dickens’ Bleak House, Eliot’s Middlemarch, and Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” (Levin 1). Any attentive reader of the Origin will realize Darwin’s prose, saturated with aesthetic and intellectual zeal, is also alive with imagery, metaphors, and rhetorical devices. In this essay, by exploring three imageries in details, the “struggle for existence,” “Natural Selection,” and the “entangled bank,” I wish to show that the Origin is not only a scientific achievement but also a literary feat; Darwin the scientist is also a writer, an imaginative lyricist.

It is important to point out that literary devices in Darwin’s writing do not necessarily conflict with his scientific arguments; in fact, they make his work appealing and comprehensible, and his ideas spread far and easily. Figurative language also softens the elements of evolution that might offend religion in his time. In his autobiography, Darwin speaks of his relationship with literature and the arts late in his life:

I have said that in one respect my mind has changed during the last twenty or thirty years. Up to the age of thirty, or beyond it, poetry of many kinds, such as the works of Milton, Gray, Byron, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley, gave me great pleasure, and even as a schoolboy I took intense delight in Shakespeare, especially in the historical plays. I have also said that formerly pictures gave me considerable, and music very great delight. But now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry: I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me. I have also almost lost any taste for pictures or music.—Music generally sets me thinking too energetically on what I have been at work on, instead of giving me pleasure. I retain some taste for fine scenery, but it does not cause me the exquisite delight which it formerly did. (Darwin 142)

This often-quoted paragraph has been interpreted as implying Darwin’s complete indifference to the arts...

Continue ReadingSewing and Writing

Over years, I haven't changed much from a little kid who loved sewing to a student who loves writing.

When I was small, I spent all day sewing clothes for dolls. I never designed before sewing but let imagination lead my needle. Whenever the clothes wasn’t in my favor, I cut the stitches and restarted sewing, again and again, until I felt satisfied. Though the needle sometimes pierced my fingers and the clothes weren’t always like my intention, these difficulties couldn’t thwart me from dressing up my dolls with hand-made clothes. With a needle and thread, I turned a useless piece of cloth into fashion, an idea into reality.

Though now I didn’t sew clothes for dolls anymore, my love of sewing was transformed to writing.

I force myself to sit down to table and pick up my pen to write whenever I lose my temper. I enjoy exchanging letters with my friends and my English teacher. Every night, in my journal, I free my words, letting the stream of consciousness guide my pen. I nitpick every word and sentence in my essays. Just like sewing, writing hurts. Writing, rewriting, and editing, they take me great effort. Nothing I have written so far comes near to perfect. My pen usually couldn’t keep pace with my ebullience. Choosing the best word to present my feeling is a never-ending process. Sometimes I could burst into tears rereading my clumsy use of words, awkward sentences, and incoherent paragraphs. But it is the sheer joy of seeing my ideas organized in paper that I want to write and write more. With a pen and notebook, I shape my ideas, altering intangibility into tangibility.

For years, I have entertained the idea of having magical powers.

I found this piece of writing on my computer. This is what I wrote at eighteen years old in response to a prompt in the Common Application for US College Admission. The prompt is: “Please share something about yourself that you have not addressed in your Common Application and which may not be revealed in a recommendation. (250 words)”

Hopefully, I am and will always be working on my magical powers :).

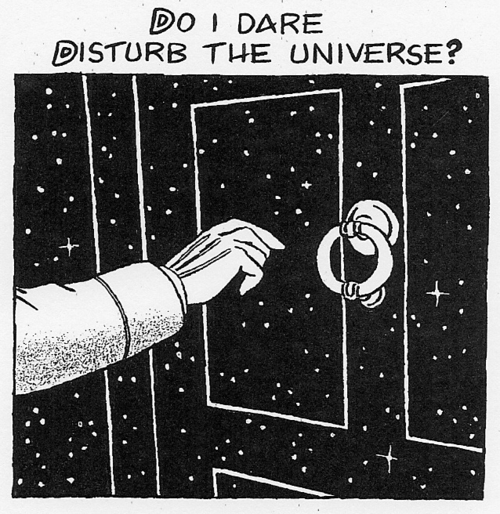

Continue Reading“The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”: an Anxiety Towards Modernity

One of the most notable figures of the modernism movement in Literature is T. S. Eliot. His poem, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”(1915), with its use of new poem form and concrete visual images, is a paragon of modern poetry. Yet, at the same time, the poem is packed with allusions to a literary past. The incongruity of the modern and the traditional elements in “Prufrock” ultimately reveals a sense of anxiety towards modernity.

On the first glance, the poem seems to be the feeling of a man who daren’t to approach the woman of his dream. Yet, on a closer look, “Prufrock” is the lamentation of an ostracized soul whose aesthetic ability and sensitivity are no match to the industrialized era. Prufrock’s hesitancy in human interaction, his sense of inadequacy, and his sexual anxiety prevail in the poem. The speaker’s uncertainty is unfolded through Eliot’s use of form and images, a combination of both the old and the new literary devices.

The poem’s form, free verse, sets it apart from traditional poems. Unlike poets before modernism that consistently comply with rules of rhymes and structure, Eliot pursues an internal rhyme scheme and an unsystematic structure. While traditional poems usually follow tail rhymes, “Prufrock” frequently contains internal rhymes, for instance:

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

In these lines, “pin,” “pinned,” and “begin” rhyme with each other, but the placement of the rhymed words is not necessarily at the end of each line. While “pin” and “begin” locate at the lines’ end, “pinned”...

Continue ReadingRepresentation of Alchemy in the Studiolo of Francesco I de’ Medici

The Studiolo of Francesco I de’ Medici is a vaulted room in Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, Italy (fig. 1). It contains an assortment of forty-four artworks including paintings, sculptures, and painted cabinets produced by thirty-one artists—twenty-three painters and eight sculptors, showcasing artistic trends of late Renaissance Florence. It was constructed from 1570 to 1575 according to the design of the Florentine court architect and painter Giorgio Vasari and the court intellectual scholar Vincenzo Borghini. It was commissioned by Francesco de’ Medici, the second grand duke of the house of Medici, the Italian dynasty that turned Florence into a global power center. Like his father, Francesco I was a fervent patron of the arts, supporting artists, building the Medici Theater, and founding the Accademia della Crusca, but he was better known for an amateur interest in sciences, particularly in “contemporary avant-garde scientific processes of transformation, including alchemy and medicine.”[1] The Studiolo reflects Francesco’s interests, containing artworks whose principal theme is the relationship between art and nature. The Studiolo of Francesco I, in its portrayal of the affinities of art and science, especially in the representation of alchemy, captures the scientific zeitgeist of the time—when the occult studies of the medieval past and the approaching modernity of the Scientific Revolution were intricately tangled.

Towards a Definition of Alchemy

In around 1610, Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) turned his newly invented telescope to the sun, observed spots on its surface, and shook the European world with his assertion of the similarity of heavenly and terrestrial bodies and the decentralized position of the earth.[2] The Studiolo, constructed before Galileo’s discovery—the event marked the beginning of the Scientific Revolution, carries with it connotation of the medieval past and the imminent modernity as we will see...

Continue Reading